Evaluation of the blocks was part of a study examining child-driven, machine-guided approach to early literacy learning. It occurred at a public charter school in Boston area. 25 children, 4-5 years old, used SpeechBlocks in their class throughout the semester. The reader can find more details about this study and its findings in our IJCCI paper listed below.

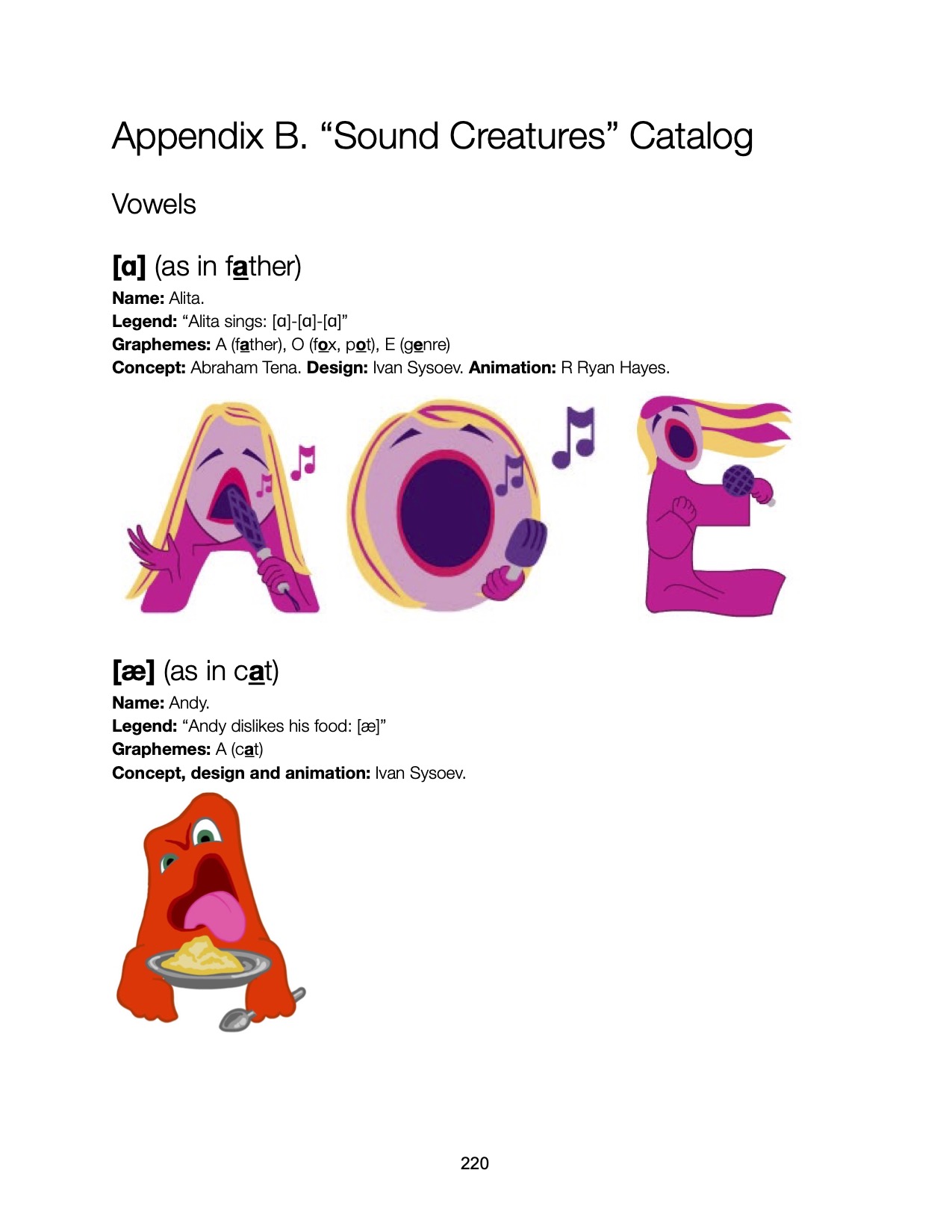

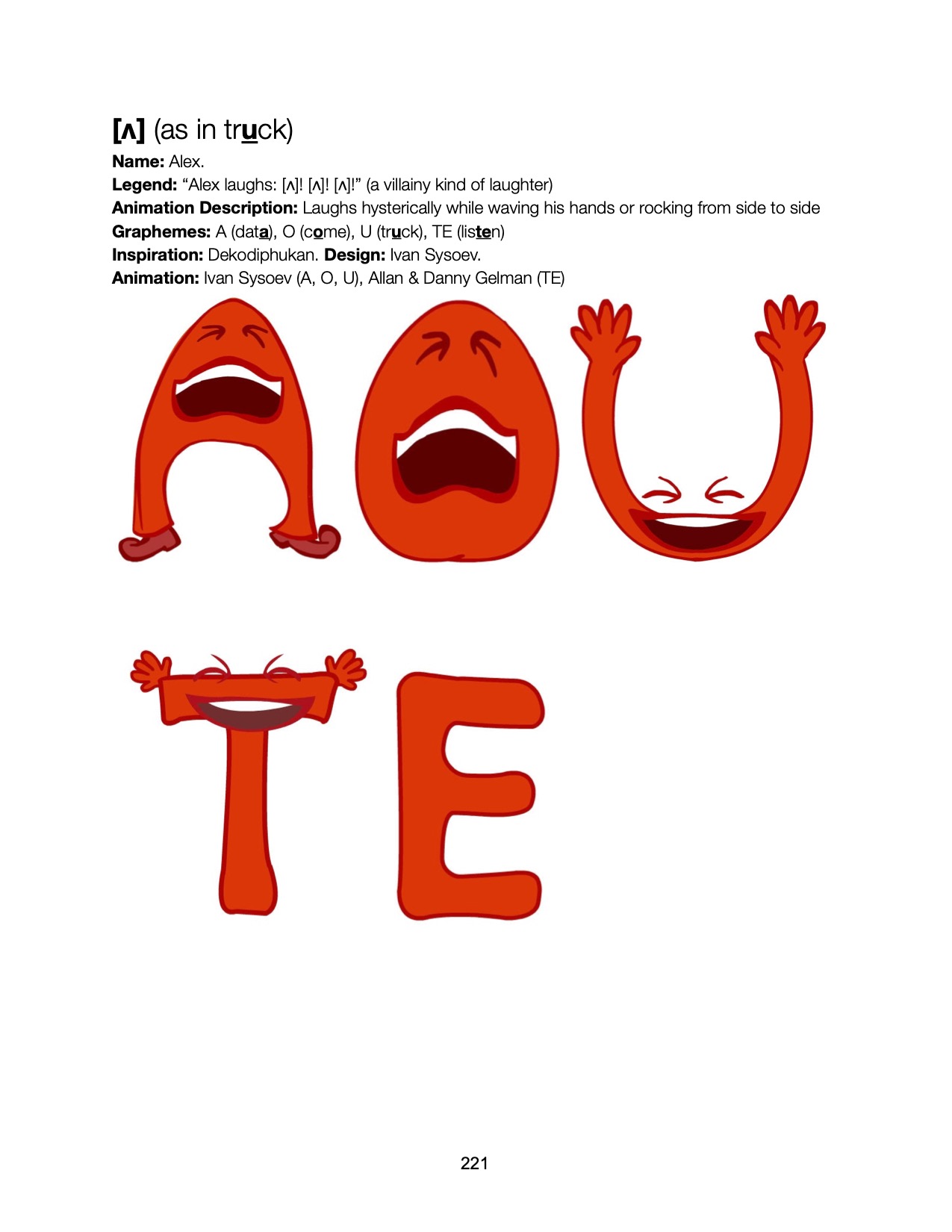

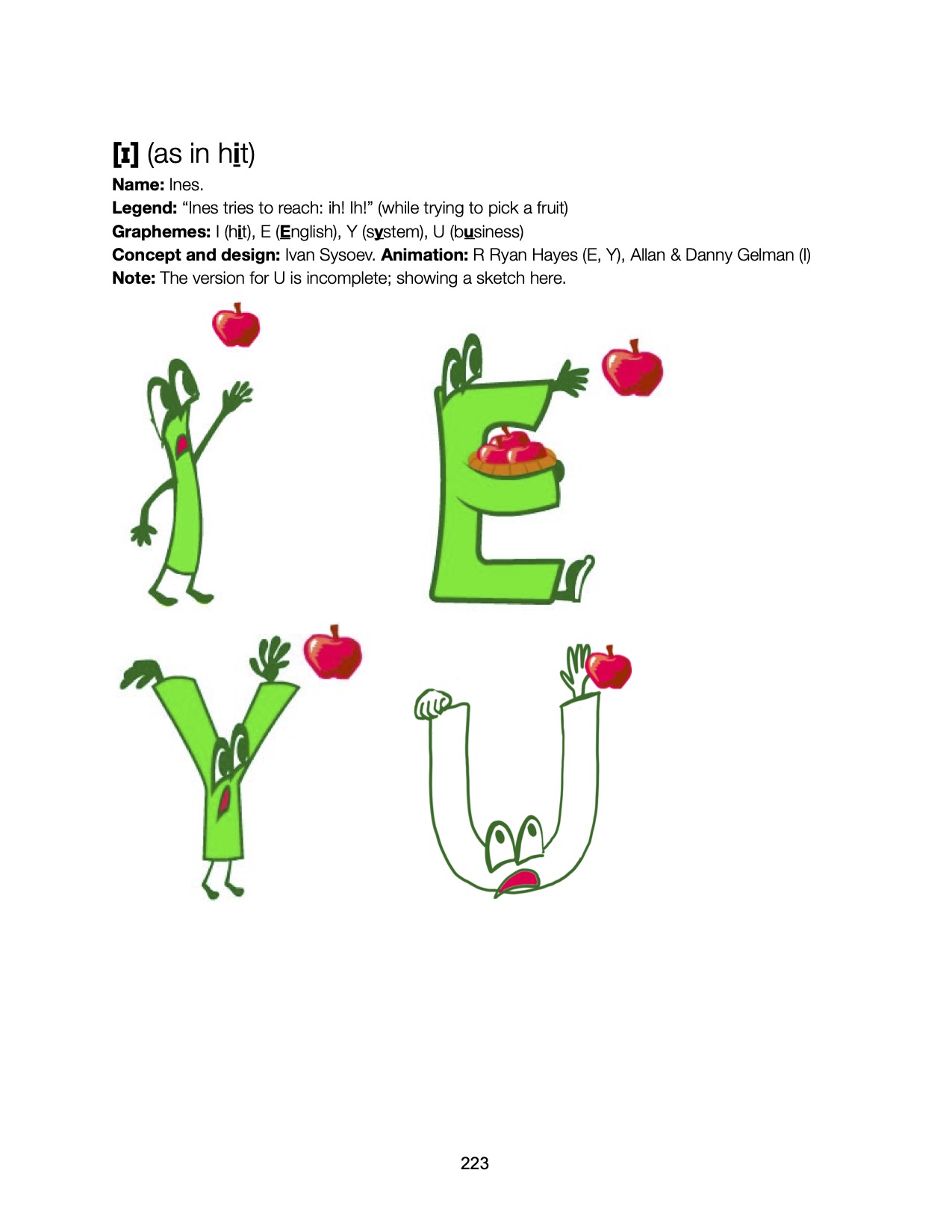

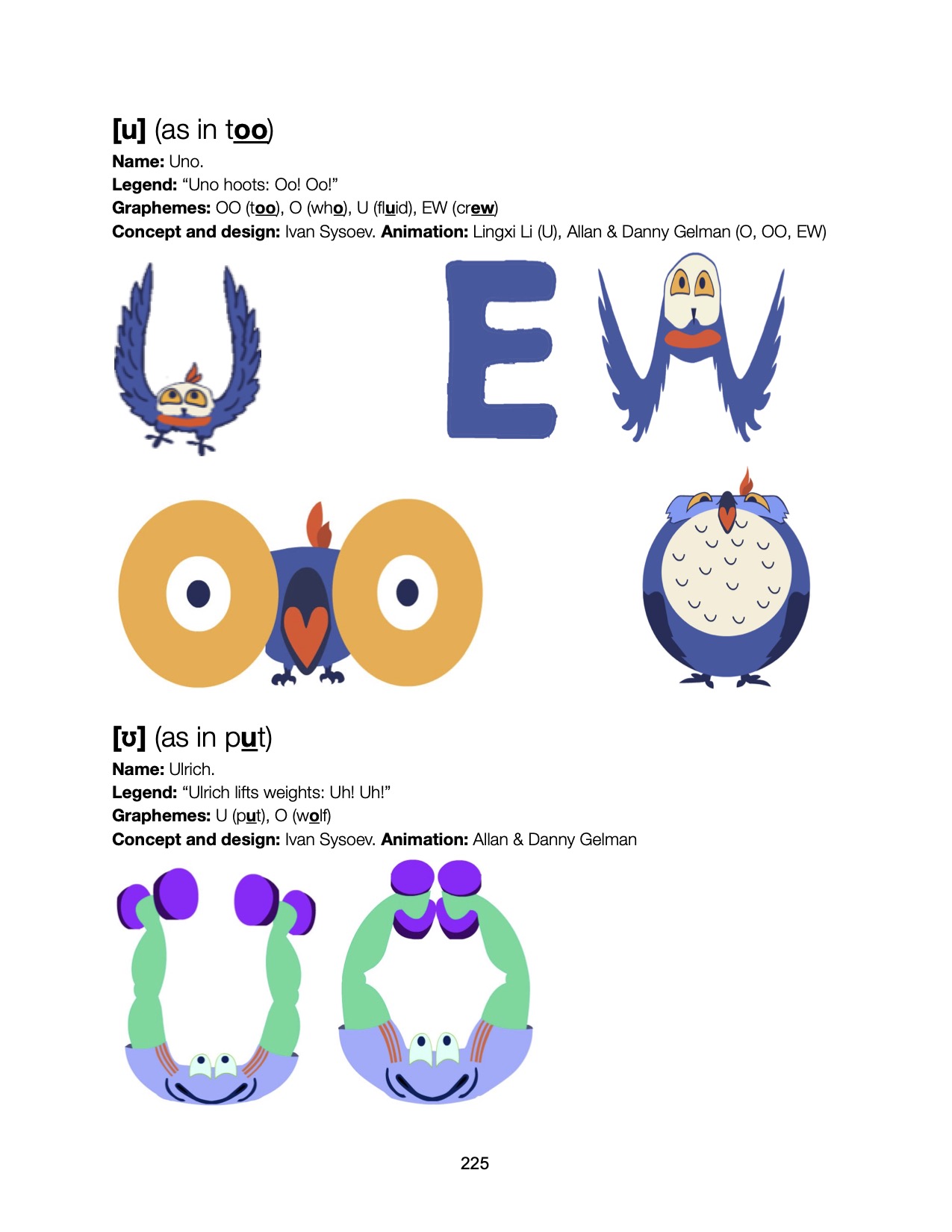

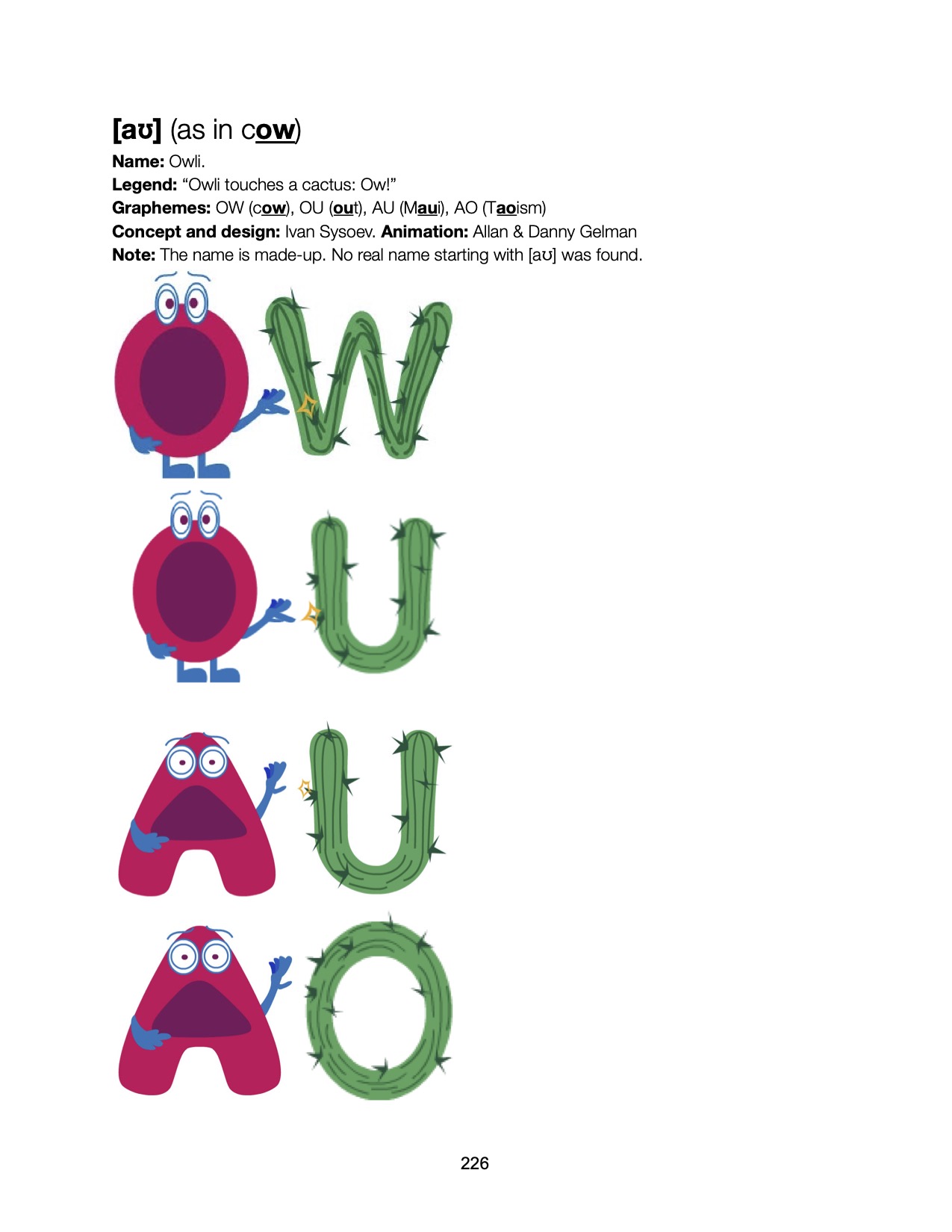

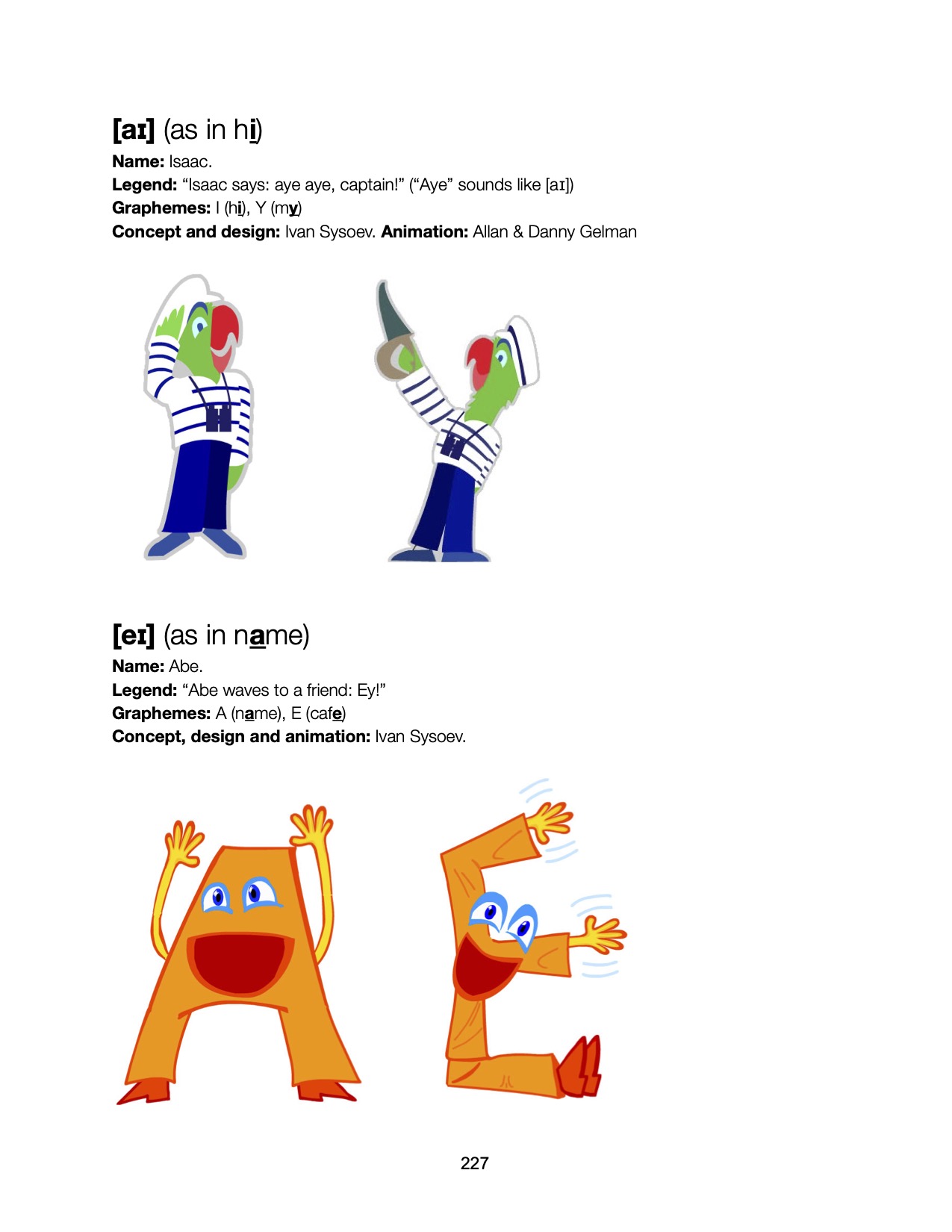

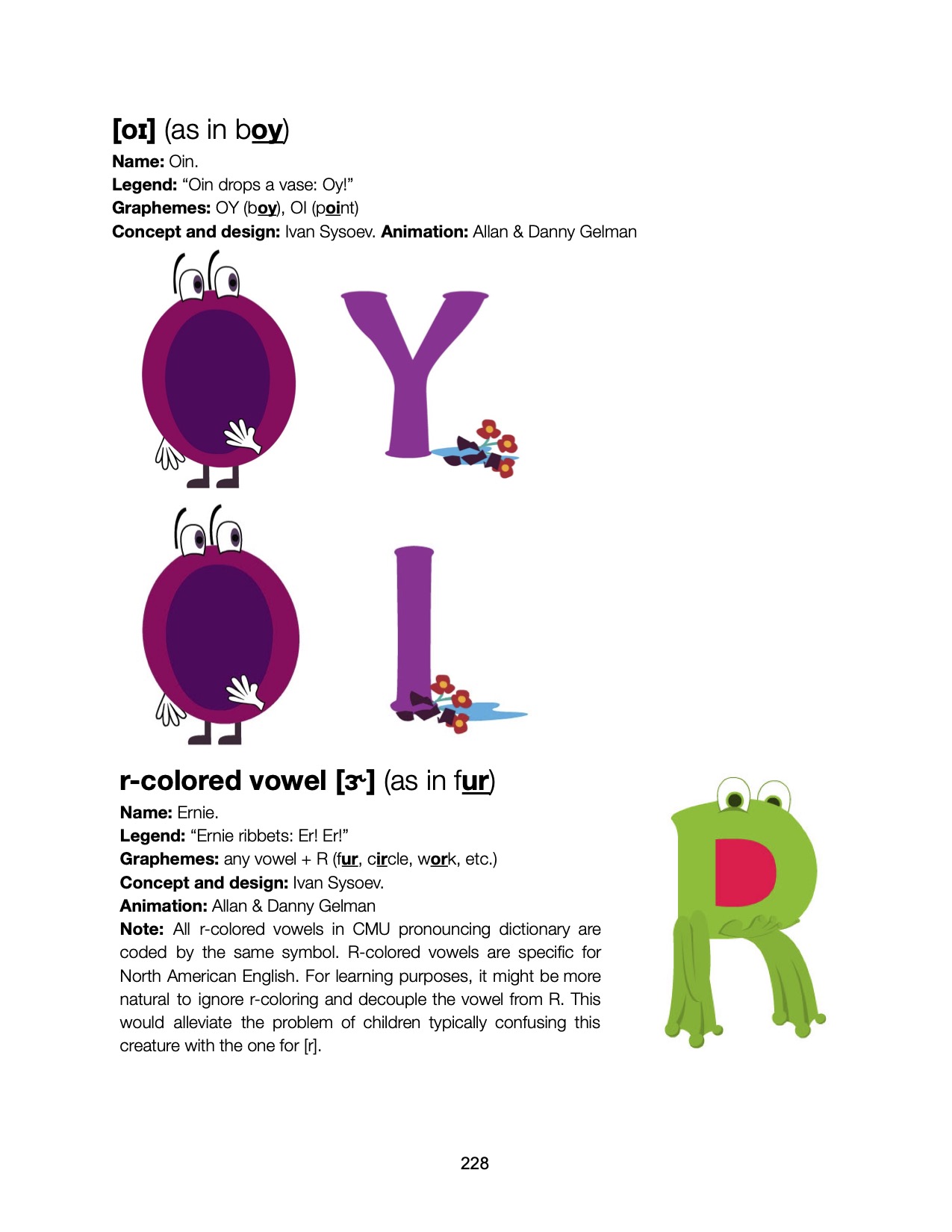

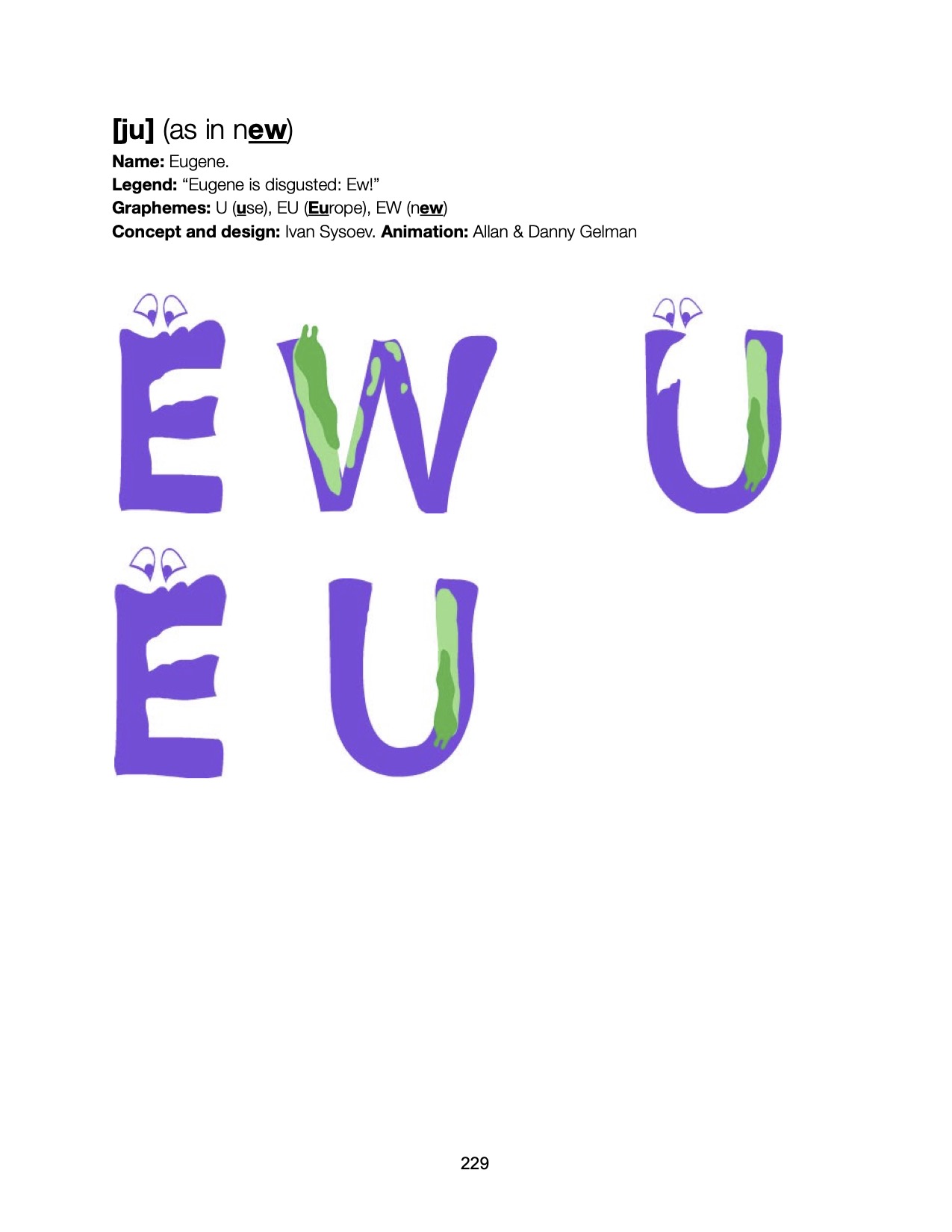

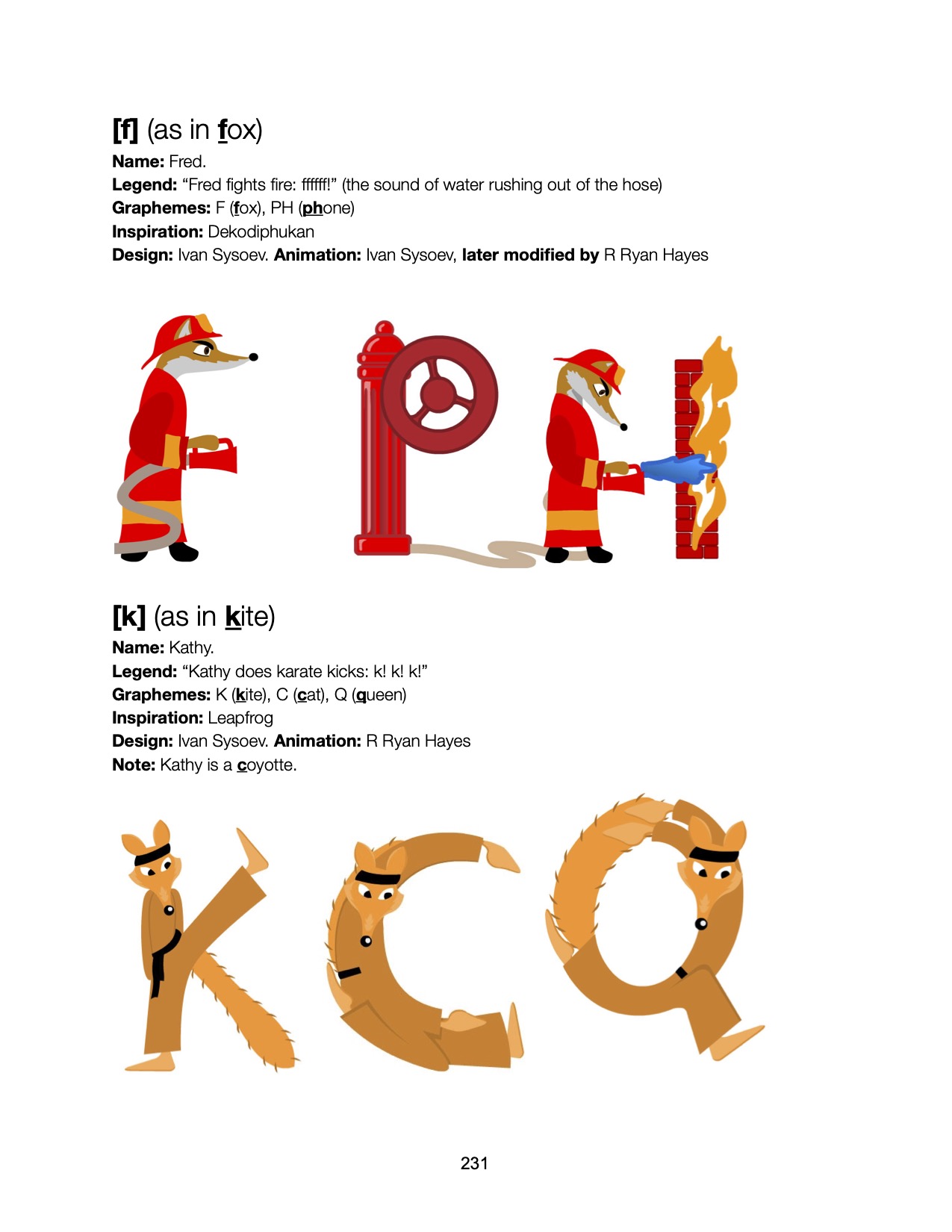

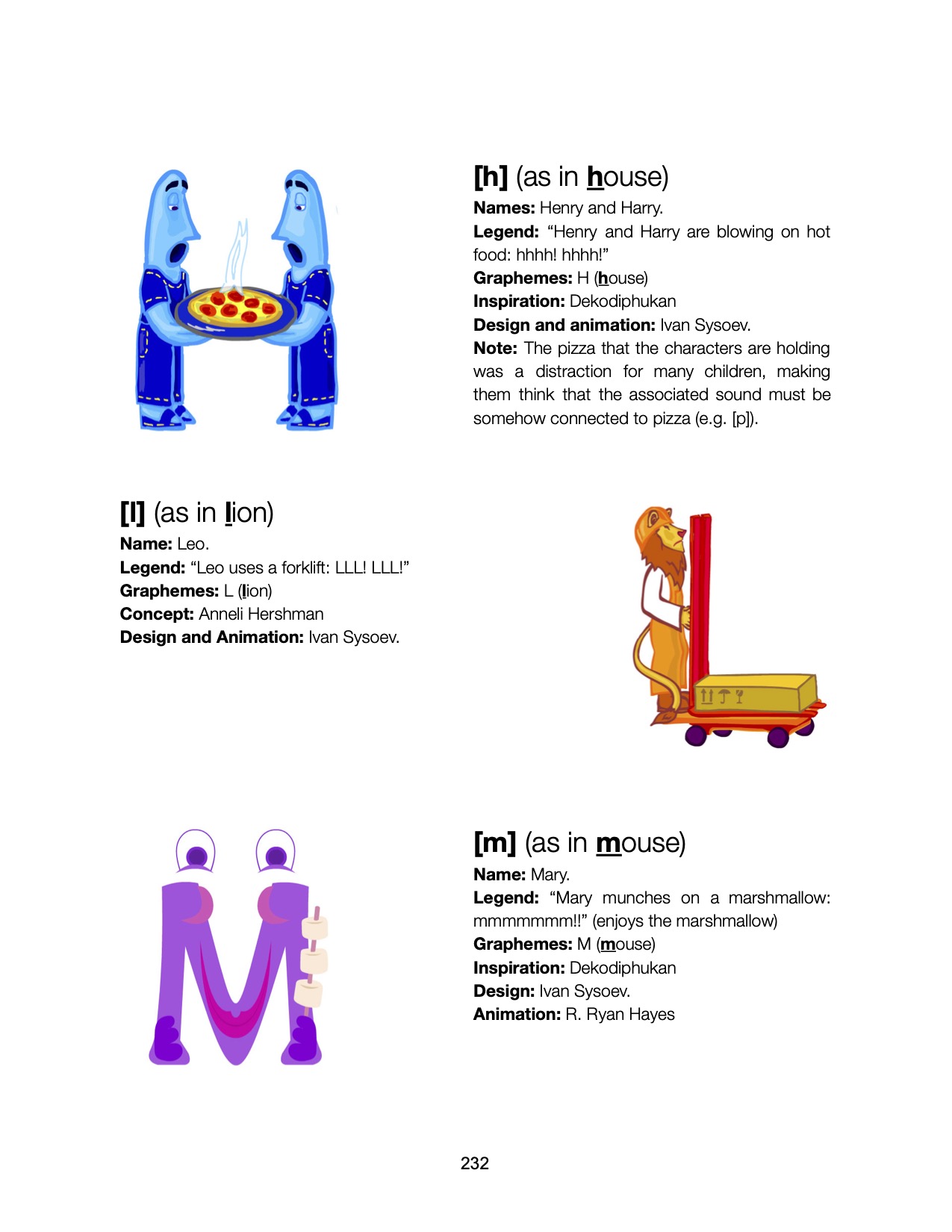

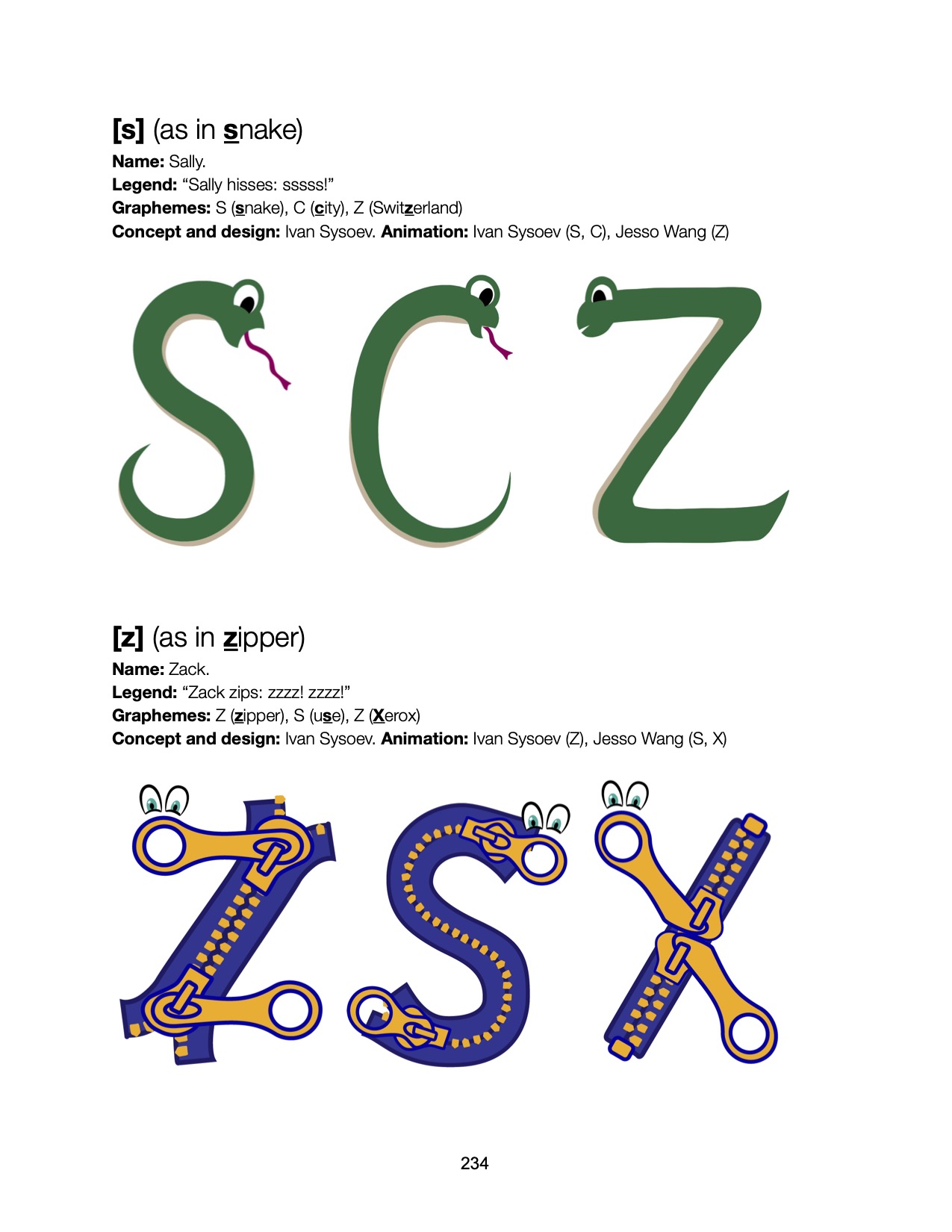

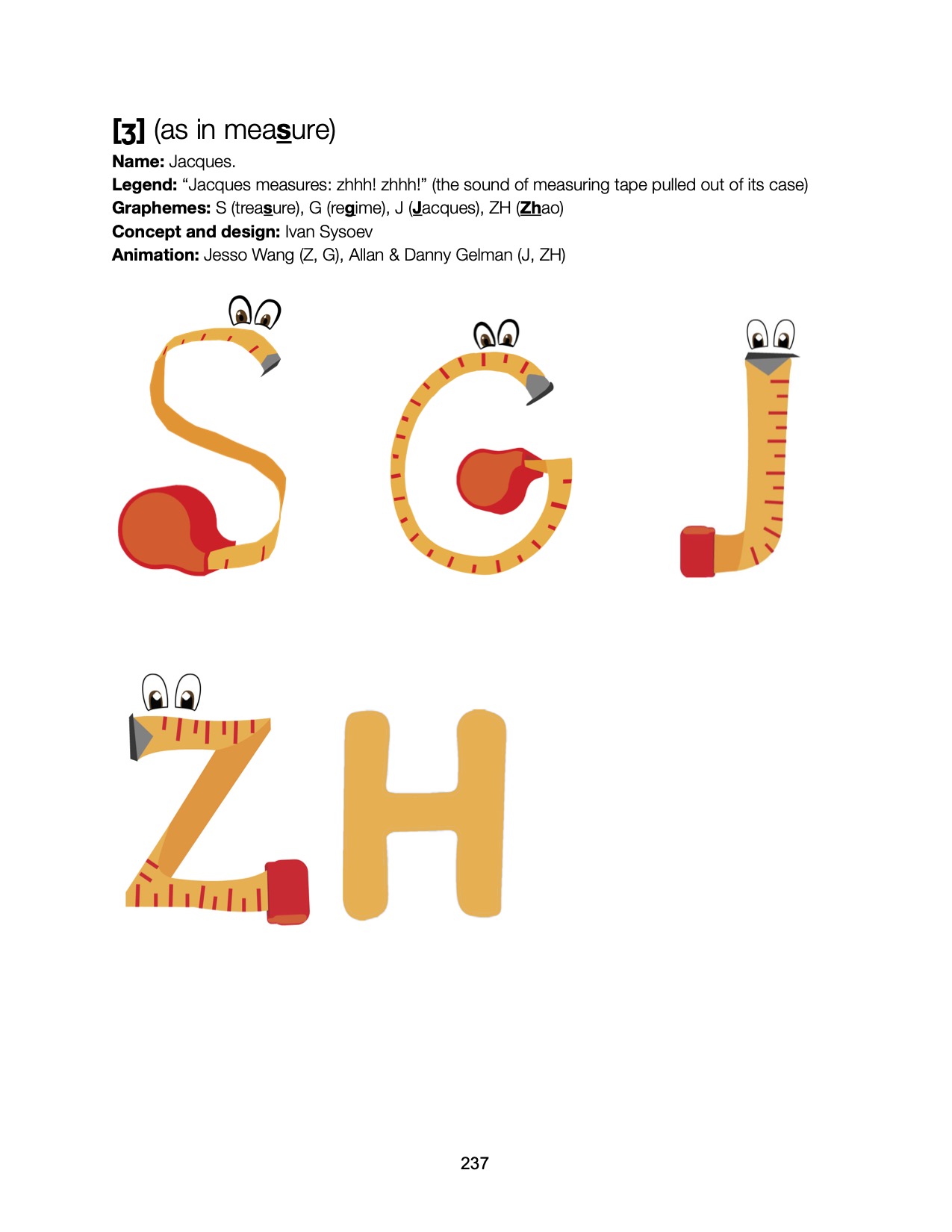

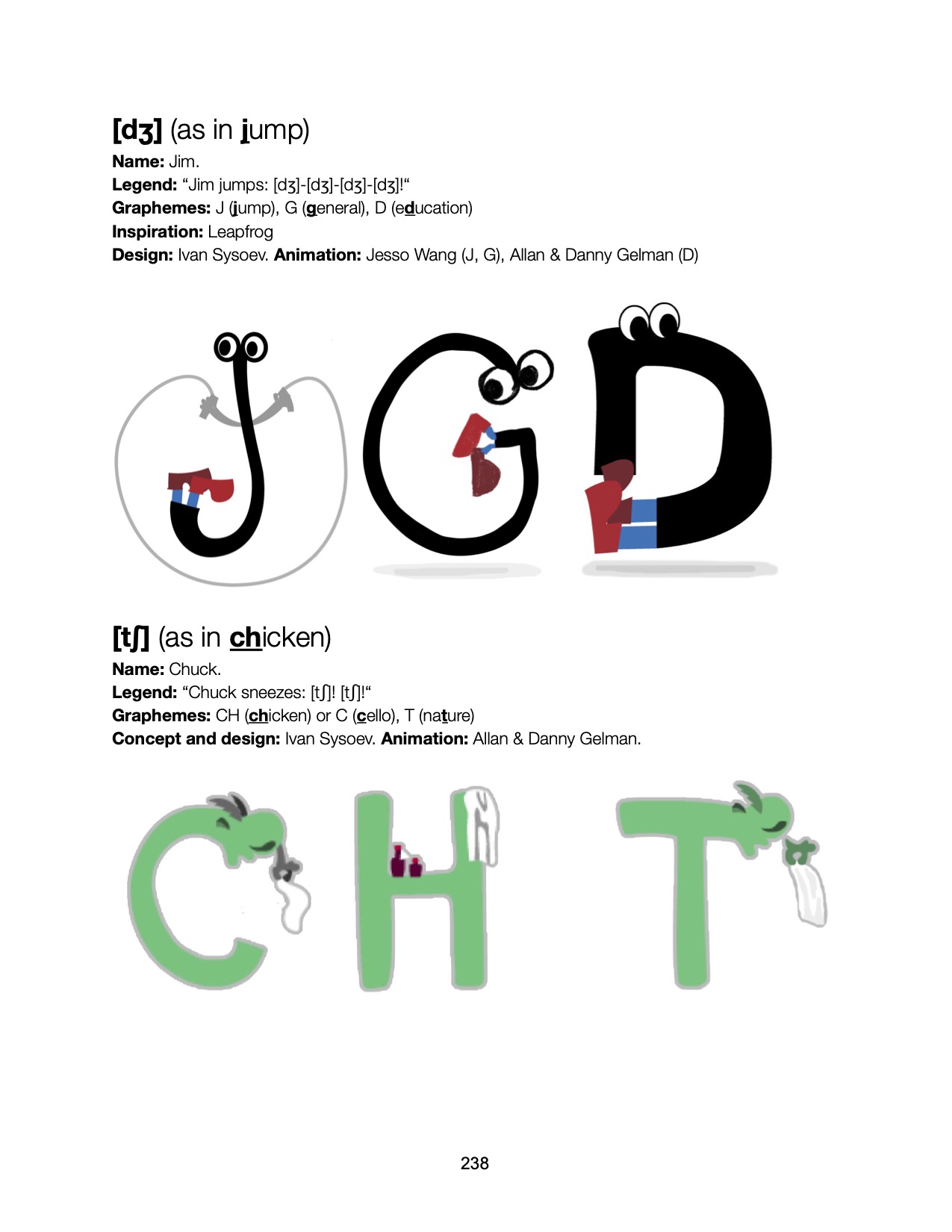

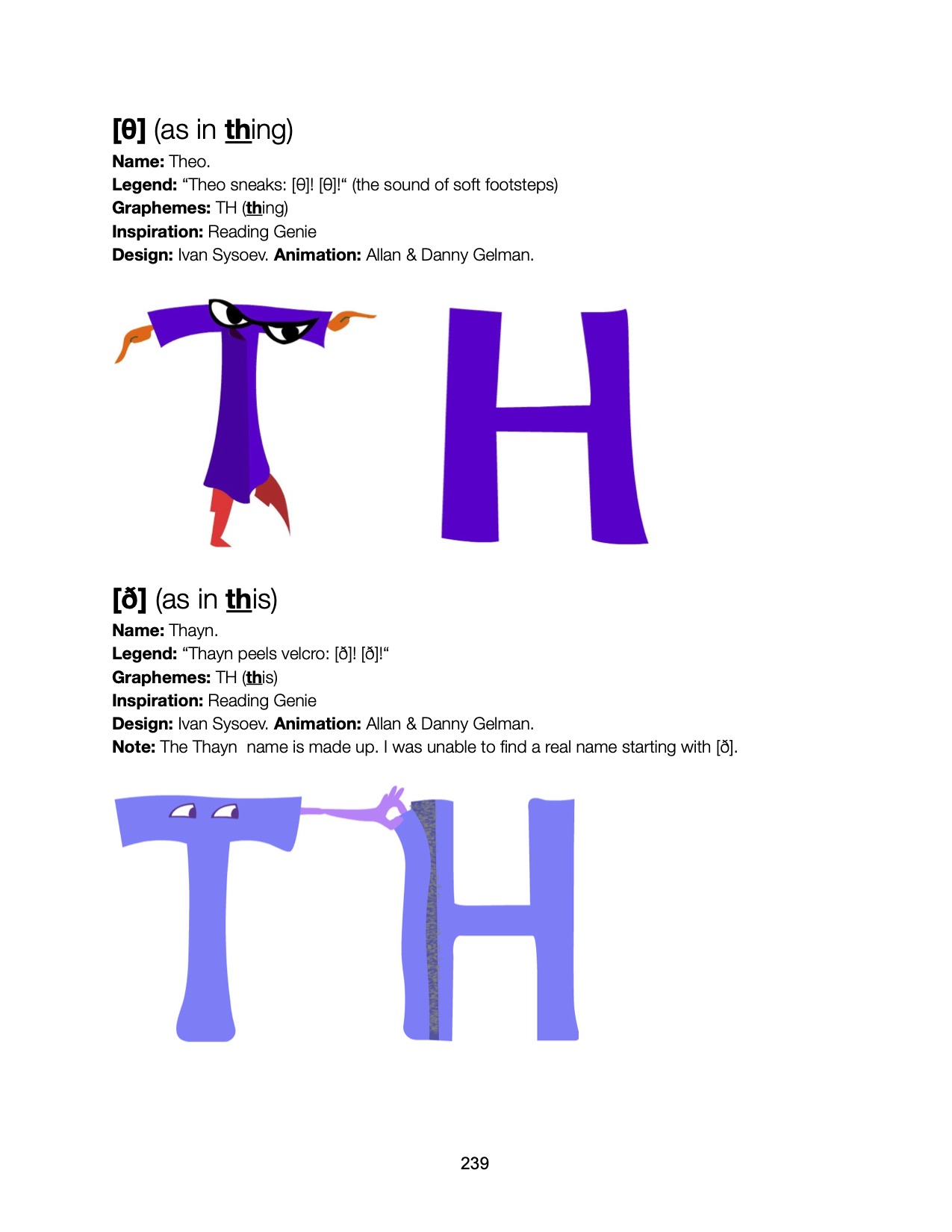

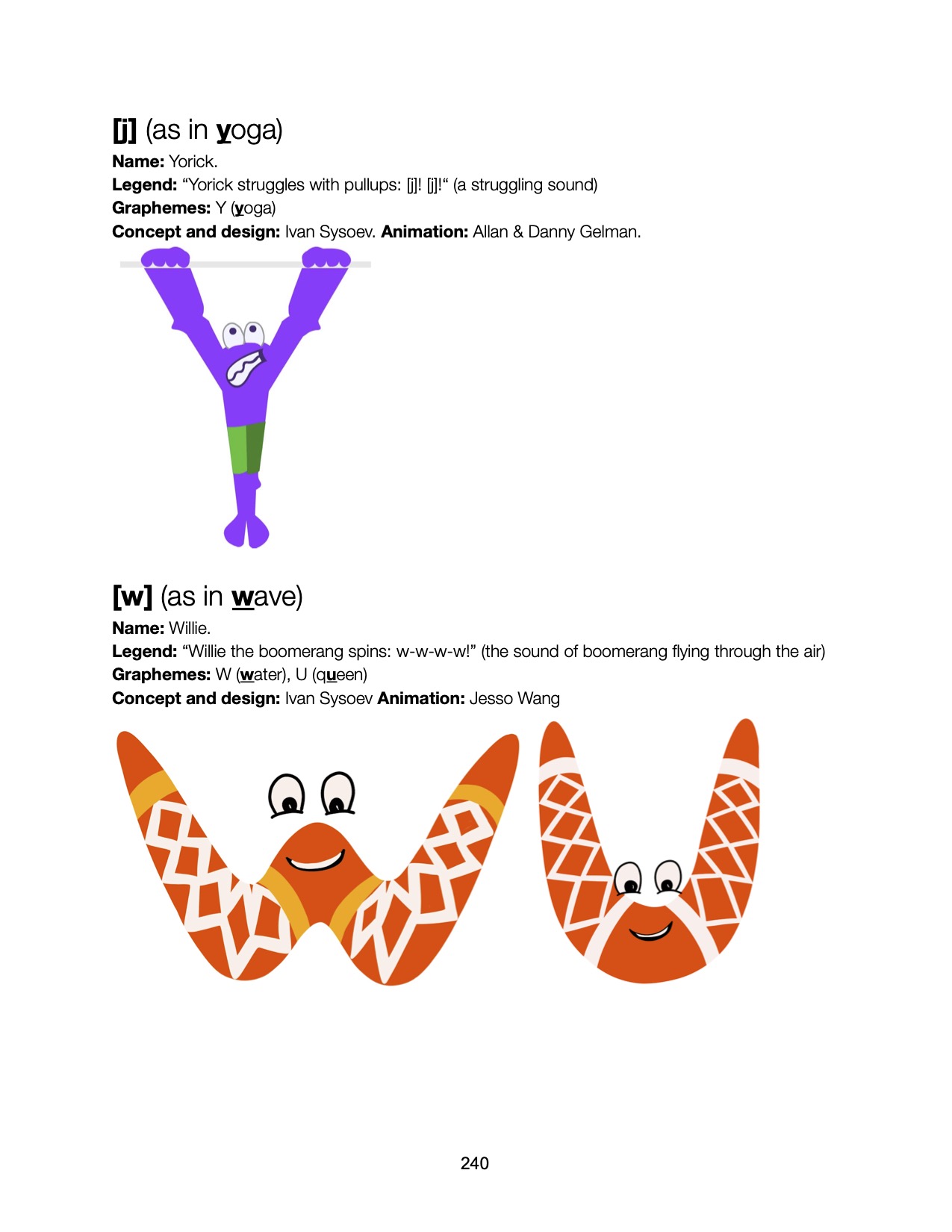

Reaction to sound creatures

Children responded to the sound creatures with interest and attention. Some of the reactions were: (1) exclamations of amusement and delight, such as “This is hilarious!” and “Mamma mia!”; (2) motor responses, such as jumping in their seats in pretend horror when seeing an animation of the snake creature; (3) mimicking the sounds produced by the creatures; and (4) commenting on the character’s actions, such as responding “Ouch! His finger is bleeding!” to the animation of the [oʊ] creature (who touched a cactus and exclaimed “Ow!”).

Subsequent interview with the children showed that most of them understood the key principles behind the creatures: that the same creature can have different forms, corresponding to different graphemes; that each of these forms produces the same sound; and that their forms represent letters. They did not, however, remembered the names that we gave to the creatures.

In some cases, superficial details of the creatures’ appearance obscured their link to phonemes. For instance, a few children responded to karate-kicking animation for the [k] creature with sounds “Hiya!” and “Pfff!”. A child building ELSA from the cartoon Frozen could not believe that Elsa starts with [ɛ], saying: “It is so ugly; how can it be in her name?” ([ɛ] it was represented by an elderly person who struggled to hear and exclaimed “Eh?”)

Useful for some, but not for everyone

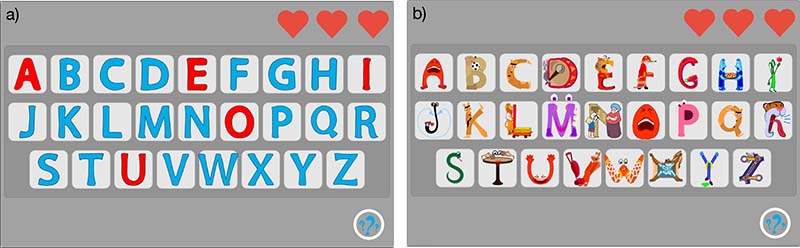

To check whether sound creatures served as useful mnemonics for phonemes, at the end of the study we administered a minigame. We asked children to find what makes certain sounds on two keyboards: one with letters, and another - with sound creatures. We measured both accuracy and speed of finding sounds.

An initial analysis showed no difference between the conditions, but observationally we noticed that some children did a lot better with sound creatures, and others - with letters. We applied a Bayesian mixed-effects model to see if this was something beyond mere chance. It turned out that this was indeed the case, and we can expect a fraction of children to benefit from the sound creatures, while for others they are not useful (see our paper for details). Unfortunately, we were unable to pinpoint what may cause this difference. Our speculation is that it might have been caused by different levels of familiarity with letters and letter sounds: those who knew them well found the creatures redundant.