The main study for this project was conducted at a public charter school in Boston area. 25 children, 4-5 years old, used SpeechBlocks in their class throughout the semester, and 32 children continued their learning as usual and were used for comparison. The reader can find more details about this study and its findings in our Computers & Education paper listed below.

Engagement, agency, self-efficacy

We observed notable engagement with the app - for example, in one case children played for 30 minutes and still wanted to go on; they asked if they could take the app home. Children proudly displayed their work to both adults and peers, made plans regarding what to build, and wanted to keep their creations and bring them home. Some children kicked, stomped, jumped in excitement and exclaimed, “Yay!” after finishing words they intended to build. Some were also proud to gather many objects on one page as evidence of their hard work. One interesting manifestation of self-efficacy was children voluntarily challenging themselves to spell difficult words. E.g., one child put his headphones down to avoid hearing the prompts. After completing the word, he proudly announced, “I did it all by myself!”

Collaborative play

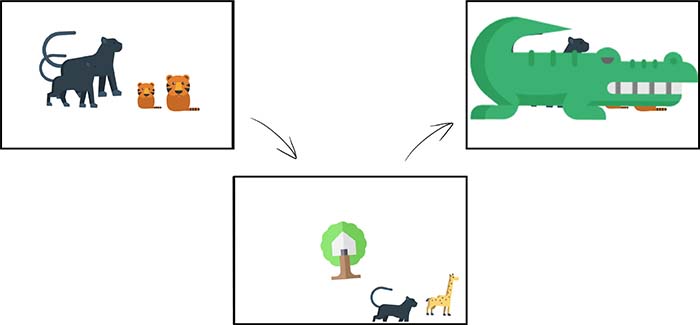

Entirely on their own, children engaged in various forms of collaborative play. They borrowed each other's ideas or elaborated on them in their creations. For example, one child built a scene showing panthers encroaching on some tigers, and showed it to a friend. The friend liked the idea and built his own panther attacking a giraffe. The first child then “one-upped” her friend by building a crocodile that, according to her, devoured all the other animals.

They also came up with small games, such as “I’m going to build your name, and you build my name. Then, let’s both build Abigail’s name”. In this way, they supported each other's engagement.

But most importantly, children directly helped each other to spell words. We saw several “leader-follower” pairs in which a more skilled child built some words and another one repeated them after her/him. These pairs talked about what they made, how they made it, and what they should do next. If the “follower” experienced any difficulties in the spelling process, the "leader" assisted him/her. This behavior created opportunities for shared learning.

Automatic scaffolding appeared to support these interactions. By fostering children’s autonomy, it allowed them to fluently respond to emerging ideas. The scaffolding machinery also made it relatively easy to explain to peers what to do by referring to the machine prompts.

What did children do?

Though children were able to use both scaffolded and non-scaffolded modes, about 85% of words were constructed with the help of scaffolding. Most of the remaining constructions were non-words (e.g. random combinations of letters). Scaffolding mechanisms thus played an important role in children's play. We saw three key categories of play with the app, roughly corresponding to three categories of players.

Word crafting focused on the creation of words apparently for the sake of it. A very popular category of such words were names. Some players experimented with long words, such as TRANSPORTATION. Word crafters enjoyed collecting the words they created on the canvas.

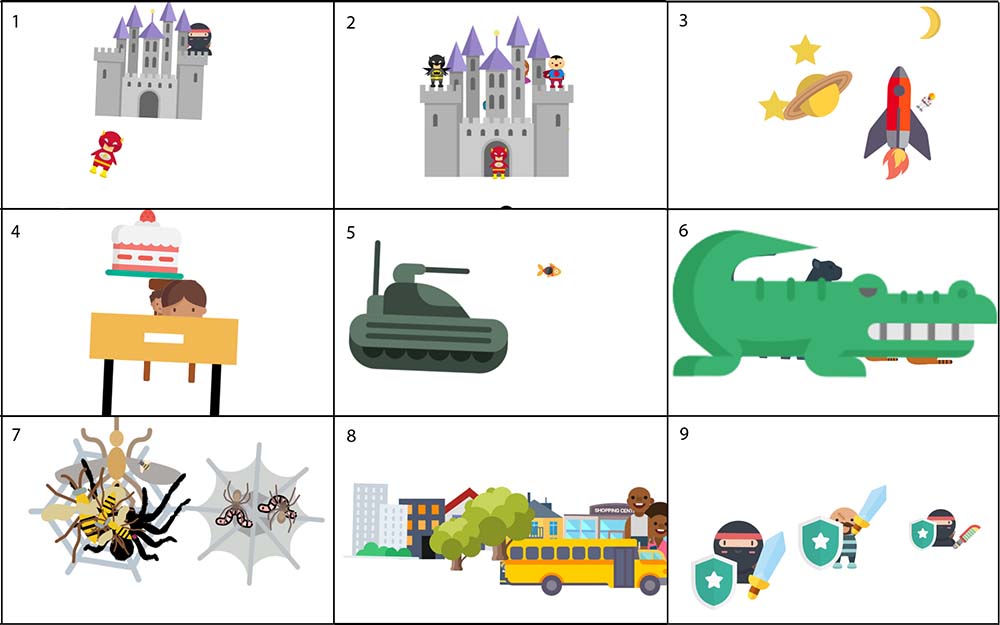

Imaginative play had two primary forms: making static scenes (such as ones on the picture below) and enactment, in which children used sprites akin to physical toys. For example, a child built several wild animals, then put a crocodile over them and enact the crocodile devouring the other animals by moving it back and forth while saying, “Chomp! Chomp!”. These forms of play were often combined by building a scene and then enacting some action within it. Children explored a diverse range of themes, such as family, home life, city, jungle and space. Among their sources of inspiration were the topics they studied in the classroom and the works of their peers.

Children typically didn't work towards implementing a pre-defined narrative; rather, the story they conveyed through SpeechBlocks evolved as they tinkered with the app. One good example is how the ninja scene (#9 on the picture above) was created. At first, the child built two ninjas and said, “They are father and son. They are practicing”. She then expressed a desire to give them weapons, and used invented spelling recognition to create SOD (sword). Then she resorted to speech recognition to build SHIELD. Afterwards, she tapped on the sword to see the related words, picked DAGGER and gave it to the small ninja. This was followed by a long exploration of the semantic association network, until she stumbled upon the word PRISONER. This discovery prompted her to exclaim, “I’m going to make a villain to fight them!”, which led to the complete scene.

For both imaginative players and word crafters, scaffolding was very important. Building scenes like the ones above required to make on the order of 10 words. In a study conducted when our app didn't have scaffolding, there were just 10 real words made by all children throughout the entire study, aside from their names and copies of words from the facilitating materials. Thus, automatic scaffolding dramatically increased the number of words children could make per session, and by means of that enabled sophisticated forms of play. By the end of our study, active players learned to use scaffolding almost completely autonomously. The teachers noted this autonomy and appreciated the resulting reduction in their workload. There was, however, one category of players for which our scaffolding appeared to be insufficient.

Impulsive exploration was characterized by a lack of systematicity: while long-term plans were voiced by the players, they were rarely followed through. Instead, children focused on short-term rewards - emotional, social and cognitive - that could be gained through interaction with the system. Such play was often unproductive from the literacy standpoint.

Impulsive explorers often passionately expressed a desire to make something ambitious, but quickly moved away from these plans or were easily discouraged by the challenges. They were usually interested in the outcome, but not the process, of word building - so they sometimes wanted their peers or the researchers to build words for them. They often didn't pay attention to directions - be it our demos, the feedback of the scaffolding system, or advice given by a peer or a facilitator - even when these directions were aimed at helping them achieve their own goals. They tried to “brute-force” word constructions by trying random actions. Finally, impulsive explorers also showed a tendency to use the app interface in unintended ways. They randomly tapped and swiped, tinkered with the hardware buttons (e.g., power off), tried to intentionally cause bugs, spent entire sessions making a single sprite big and small and used the OCR interface to “take pictures” of each other.

Impulsive exploration was more often exhibited by kids with lower phonological awareness and executive functioning. These attributes were also associated with lower levels of learning from the app. It is likely that the distracted behaviors impeded learning. A question remains whether improvements to the design can alleviate these problem. One possibility is that it was a by-product of our scaffolding system being not sufficiently adaptive to the child's skill level, making intended activities were too difficult for children with lower skills. In the future, we plan to investigate whether a more adaptive scaffolding could help with the situation.